Armory Center for the Arts

Armory Center for the Arts

In 2018, the Armory Center for the Arts in Pasadena presented a very successful installment of the touring exhibition Akunnittinni: A Kinngait Family Portrait, organized by curator Andrea R. Hanley (Navajo) for the IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where it was originally presented. West Baffin Eskimo Cooperative caught up the Armory’s Director of Exhibition Programs and Chief Curator Irene Georgia Tsatsos, to learn more about the Armory and to discuss the popularity of Inuit art in Southern California.

Let’s start with some details about your organization, the Armory Center for the Arts in Pasadena. What would you like us to know about?

The Armory is a community based contemporary arts organization with a more than 30 year history of serving a wide range of audiences. Our building is a multi-use facility that affords us the opportunity to present an annual program of exhibitions, which are complemented by a schedule of lectures, screenings, concerts and other public engagements. We also offer creative classes to students of all ages – children, youth, adults and families. And in addition to our onsite initiatives, we conduct a tremendous amount of programming offsite in different neighborhoods and in partnership with local community centers, service agencies and schools. These satellite initiatives allow us to contribute creative content to many non-arts organizations, while at the same time reach a broad audience and expand our own Armory community.

One of our offsite programs, presented in partnership with local schools, gets students out of classrooms and to outdoor environments to learn about the earth and physical sciences through the visual arts. Called Children Investigate the Environment, it’s a signature initiative that’s almost as old as the organization – we’ve been presenting it for some 30 years now.

I would say that what gives the Armory its strength and relevance is its broad range of stakeholders and the diverse community that we serve. We really are an institution that is so many things to so many people, yet we come together into a cohesive whole to present and teach art by working through a lens of cultural equity and inclusion. The work that we do bringing people together is very important and whether those connections are happening in the building or offsite in the community, we always strive to welcome and provide an engaging experience for everybody.

As an integrated exhibition space and teaching facility, can you tell us more about how those two streams of activity work together? And perhaps give us some details about the community art education programs at Armory?

That is a very important part of the Armory structure, since our teaching artists commonly use the exhibitions as inspiration for curriculum development. For example, students who participate in studio sessions will take a field trip through the galleries, before they’re open to the public, to engage in a conversation around the themes in the work. Then they move into the studio where they develop art projects based on their experience in the galleries. This approach becomes a way of emphasizing storytelling alongside technique, which creates a very rich experience for our students. We've been doing this for a long time now, it’s become a seamless part of our method, and we regularly hear from adults who reminisce enthusiastically about the work they made at the Armory when they were kids. In fact, our Executive Director, Leslie Ito, recently told a story about speaking to our new HR representative, and he was so excited about working on our account because he visited the Armory as a kid. We hear those kinds of stories all the time – they reflect the long-term investment that the Armory has had in the community as an inclusive meeting place and as a site for learning and discovery. I would say those themes are evident throughout the institution, whether they manifest in classes, in exhibitions or in related programs. I think overall, we do a terrific job at fostering curiosity about the world around us and about how other people live. We really embrace the storytelling that comes out of that curiosity, and the listening that accompanies it, which leads to empathy and understanding, something we need more of in the world right now.

Let’s talk about the Armory and its relationship to Indigenous arts. What are some of the ways that you’ve showcased Aboriginal creators?

Enhancing our conversations with members of Indigenous groups in our area is a very important part of the Armory’s mandate and we’re seeking to further include those voices in all layers of our activities. Currently, I'm in the earliest stages of a four-year research project that’s part of the Getty’s Pacific Standard Time initiative, which has strong elements of Indigeneity. The project starts with seeds and the knowledges that accompany them, including Indigenous storytelling histories, and addresses themes of sustainability. The research will inform a capstone exhibition as well as a number of others, along with related programs and events.

I previously mentioned one of our oldest programs, Children Investigate the Environment (CIE), which includes visits to the nearby Hahamonga Watershed Park, the historic site of a former Tongva-Gabrieleño village. Our CIE curricula are developed in tandem with members of the Tonga-Gabrieleño community.

I think you're way ahead of us in Canada. For example, the integration of land acknowledgements still isn’t customary here in the States. It’s only now that this is starting in the Los Angeles area – just starting – to be done with any regularity. It is encouraging to see growing recognition around the history of the land we're on and the people who have lived here for millennia, and a growing understanding that the complicated and limited colonial/settler view is not the only perspective.

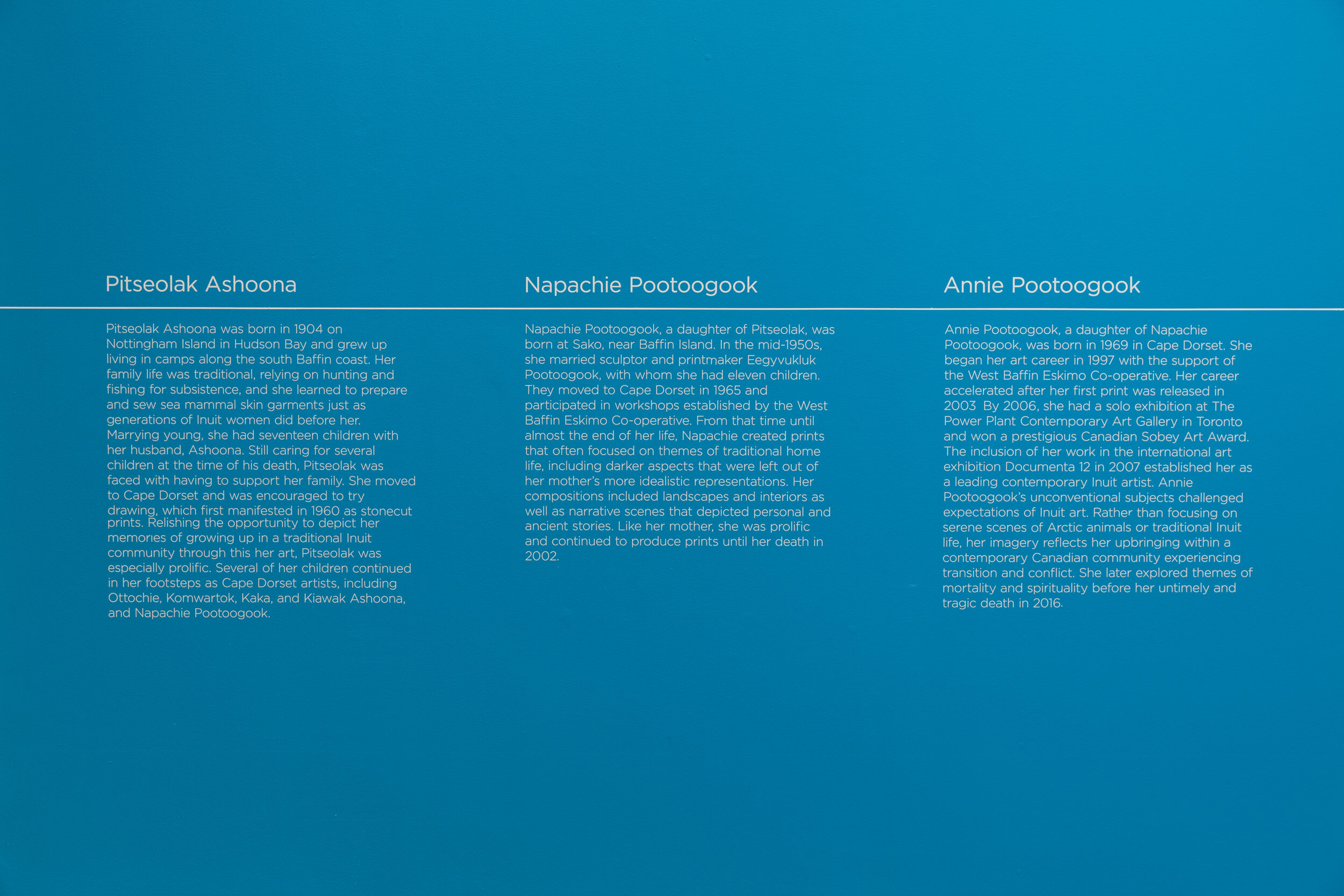

In 2018, you presented the exhibition Akunnittinni: A Kinngait Family Portrait that featured the work of Cape Dorset Inuit artists Pitseolak Ashoona, her daughter Napachie Pootoogook and granddaughter Annie Pootoogook. What was the community response to that exhibition?

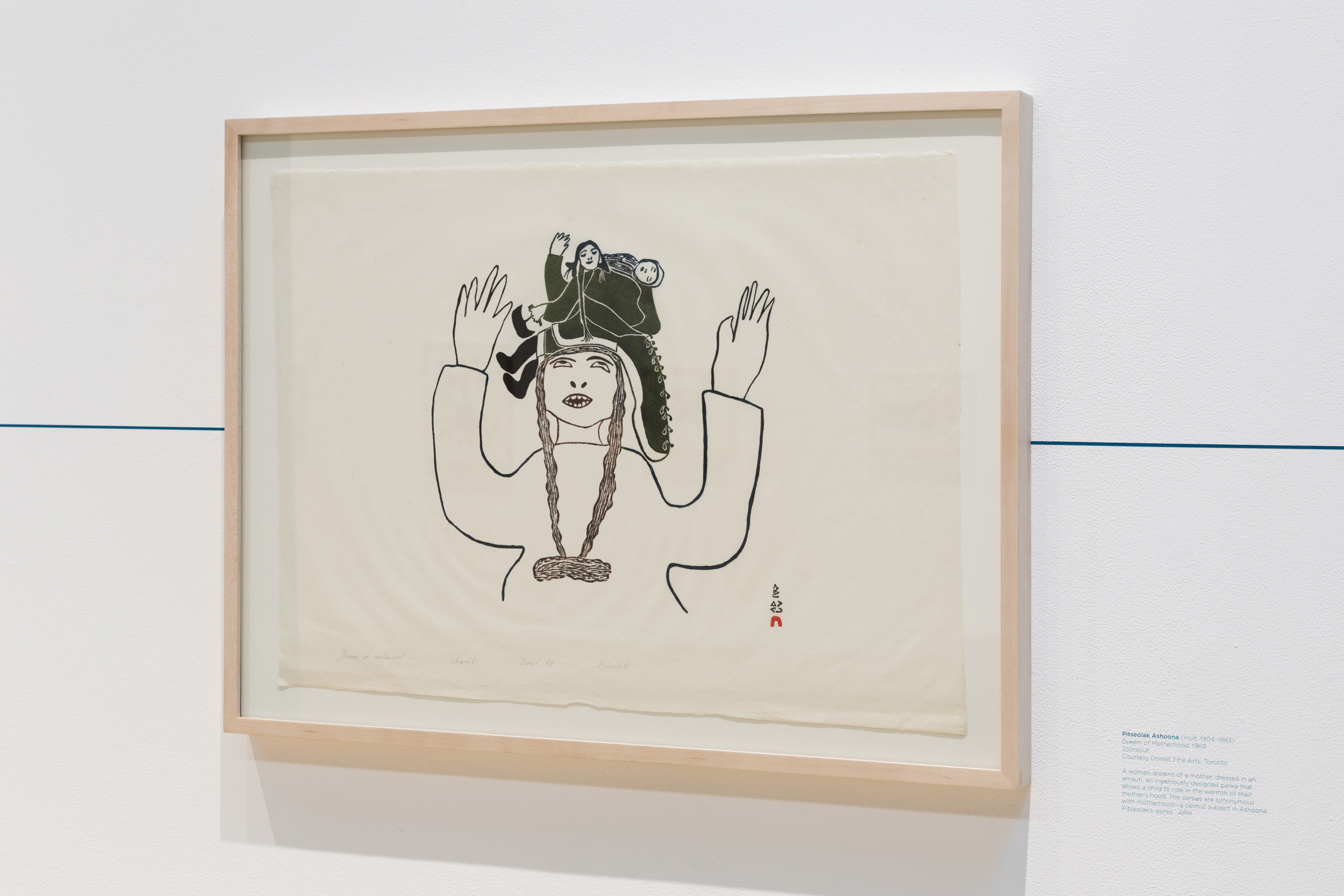

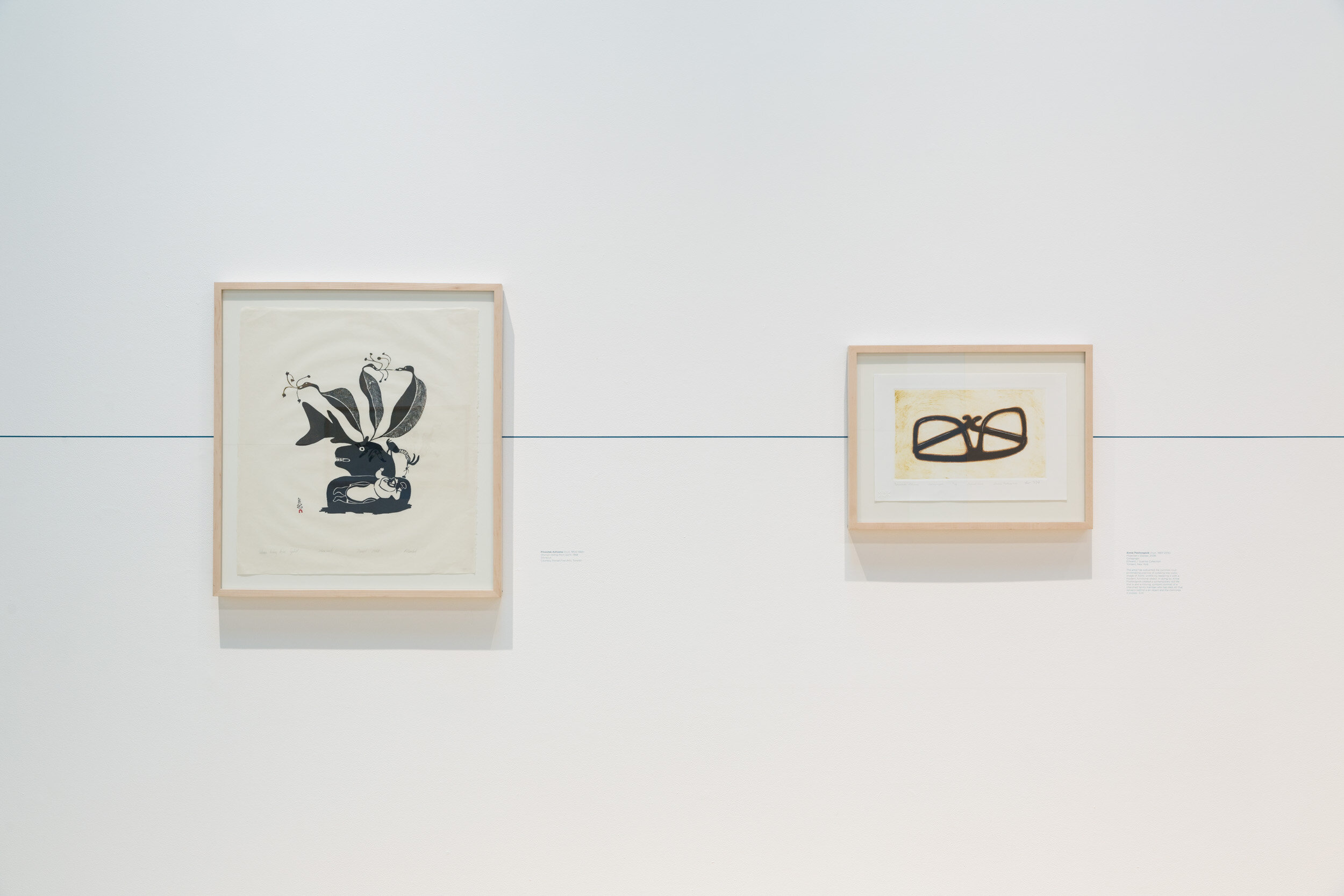

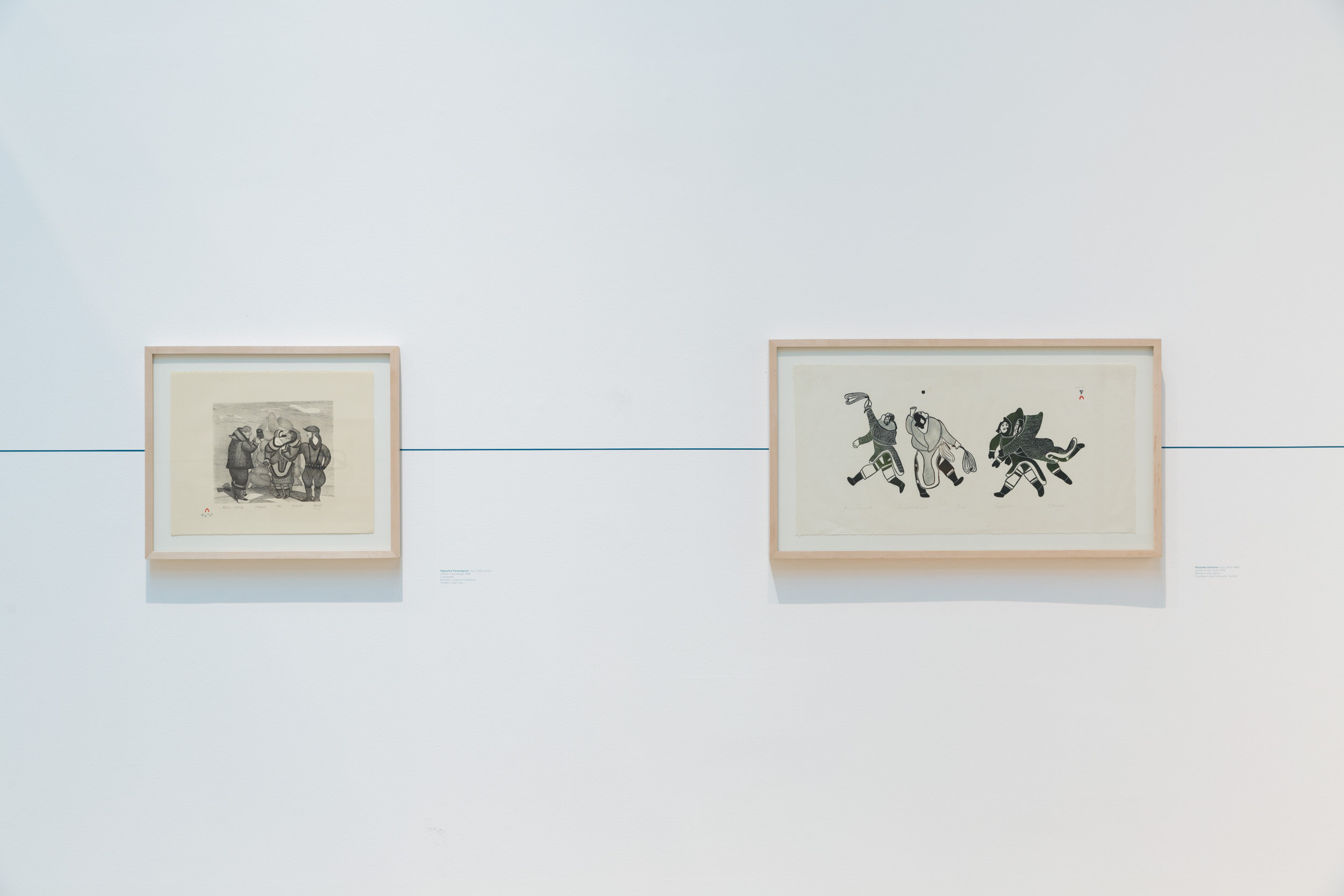

Oh, it was such a rich experience for us, hosting the exhibition. The public response to the show was just overwhelming. I still have people tell me how much they loved it. And it's so interesting because in a way it was a quiet exhibition. It was modestly scaled with a unique intimacy, while at the same time there is something so profound about the images, which are such compelling portals into the lives of the artists, and life in the North. It was quite clear that Akunnittinni resonated with the Armory audience and we heard lots of appreciative feedback that we were able to present the show in Pasadena. And it wasn’t just the general public – our teaching artists, our board members, our students were all moved and inspired by its content. A number of people who don't visit regularly or don’t visit every single exhibition at the Armory made a point of telling us that they came to that specific show because the content was captivating to them. So Akunnittinni really distinguished itself in a lot of ways and has become a significant example of the Armory commitment to diverse, particularly Indigenous, creative voices.

In our current circumstances, lots has changed in the cultural sector with lots of venues closed, programming on hold and a move to more robust online initiatives. In that context, are there concerns or opportunities that you’re thinking about, moving forward?

There are certainly many concerns right now, including significant threats to the overall stability of the cultural sector. But at the same time, we’re looking for the opportunities in this current situation, you have to. As the temporary suspension of in-person activities became a reality, we looked to online programming as a necessity, like everyone else. We have seen the power of being able to connect locally and globally around themes that matter to all of us. There’s been an unexpected benefit in moving online – it’s changed the way we think about connections and given us new ways with which we can access each other. There is an opportunity for greater inclusion and access with technology and the online realm, although to be clear the pandemic has also revealed profound inequities in access and resources. At the Armory we’re thinking about how to harness new opportunities and, at the same time, how to support those in our community who lack access and resources.

At a time of so much uncertainty and disruption, we have to find ways to fortify ourselves and find joy and beauty and peace, which the arts has always helped us do. The arts shed light in darkness and help bring words and images to incomprehensible situations. So, we’re finding ways to do that despite circumstances, and in fact seeing a number of unexpected opportunities to enrich what we do through virtual programs and presentations as well as safe in-person activities, making new relationships and deepening those that already exist. Sure, this was a forced change for us, but not only have we made the best of it, we’ve learned some lasting lessons about equity, access, resilience, and inventiveness.